Blue distance

UTS Gallery, Sydney

3 June - 4 July 2014

catalogue

This exhibition explores the disparity between spatial and temporal experience by looking at the prefabricated ruin as a catalyst for the psychological resonances implicit in architectural follies and ‘eye-catchers’ of classical structures.

If longing were a colour it would be blue. The title of this exhibition references Walter Benjamin’s invocation of the ancient topos ‘blue distance’–Fernblick ins Blau or literally translated to ‘the far-gaze into the blue’–as an expression for romantic longing.

The scope of leisurely travel in the 18th century had a two-fold effect: it brought the curious eye closer to foreign places while concurrently perpetuating an armchair traveller of those who weren’t able to partake in such journeys. Ruins became sought after sights where picturesque-hunters experienced beauty and the ‘Sublime’. Mock ruins were those that pretended to be the remains of an original building but were in fact constructed in a dilapidated state. Built for decoration and pleasure on affluent estates, follies represented different continents or historical eras: structures suffused with fabricated age and sentimentality for that which was seen and experienced abroad–but in other cases, only imagined. Philosophically, an ‘eye-catcher’ could summon one to traverse social and temporal contexts, thereby linking the present and the past.

This exhibition looks at the ruin as a metaphor for social and cultural phenomenon. Throughout history global movement and travel has had a profound impact on the basic ontological concepts of space and time. Contemporary global cultures however seem ever more transient, moving back and forth between places with the notion of home becoming more distant and sometimes absent, replaced perhaps by the new technologies of connectivity. Miwon Kwon uses the concept ‘wrong place’ to observe how one may imagine a new model of ‘belonging-in-transience’–countering a rooted place of belonging which we may become nostalgic for, and embracing a nomadic ‘fluidity’ of movement, while remaining antinostalgic. The waning of our ability to locate ourselves in the world is also examined by writer and critic Lucy Lippard suggests that this is a result of our sense of identity being fundamentally tied to places and the histories they embody. Voluntary migrations and forced movements therefore have uprooted our lives from specific local cultures and places and placed us is a state of flux. Does this lack of belonging, continuity–and loss of anthropological place–create a new form of nostalgia specific to the contemporary age?

Ernst Bloch suggested the existence of a utopian impulse: a tendency for humans to long for and imagine a life otherwise. The desire for a better or different way of being is inherently tied to longing and may be linked to a nostalgic sensibility. Utopia, according to Bloch, is a quest for wholeness and heimat. This German concept implies the connection a human being has towards a specific social unit or place: a quest for being at home in the world.

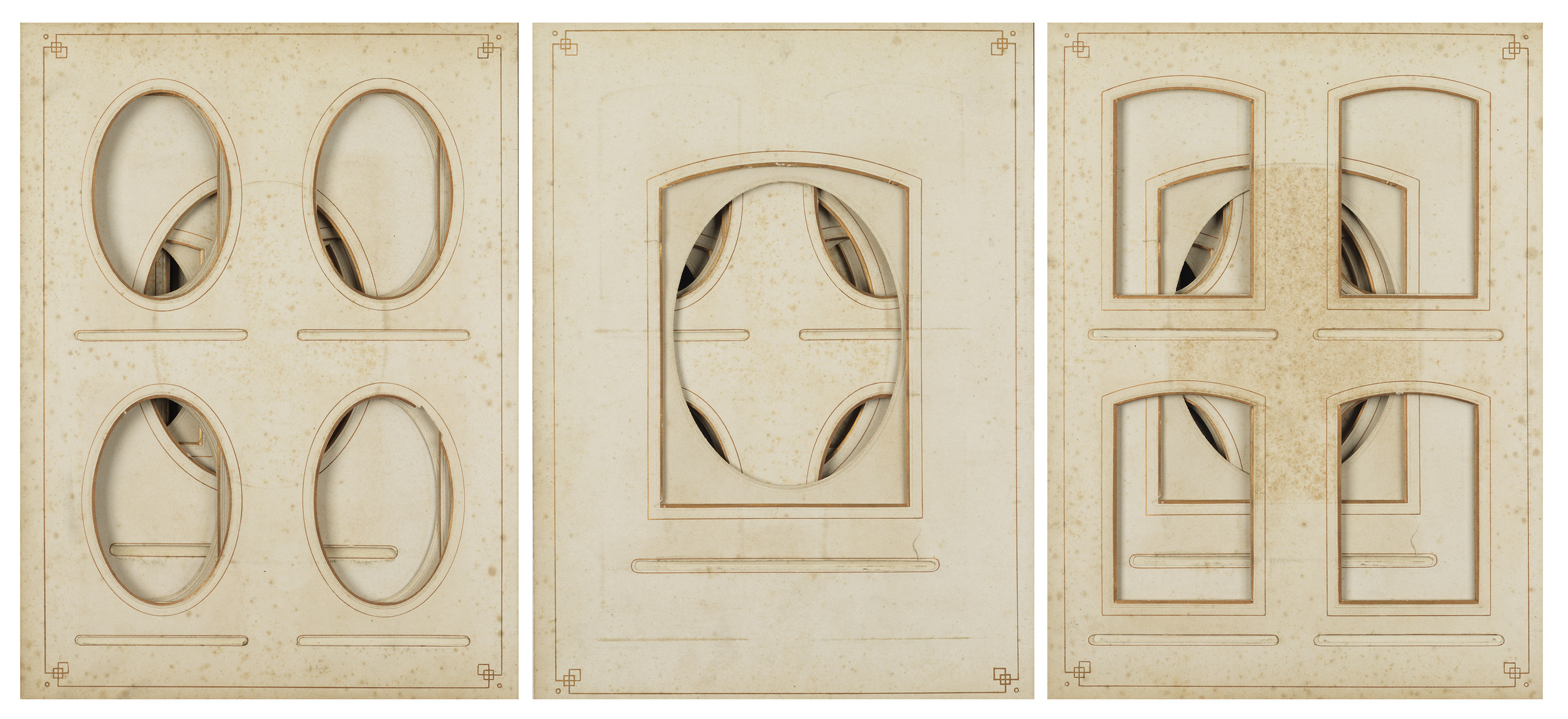

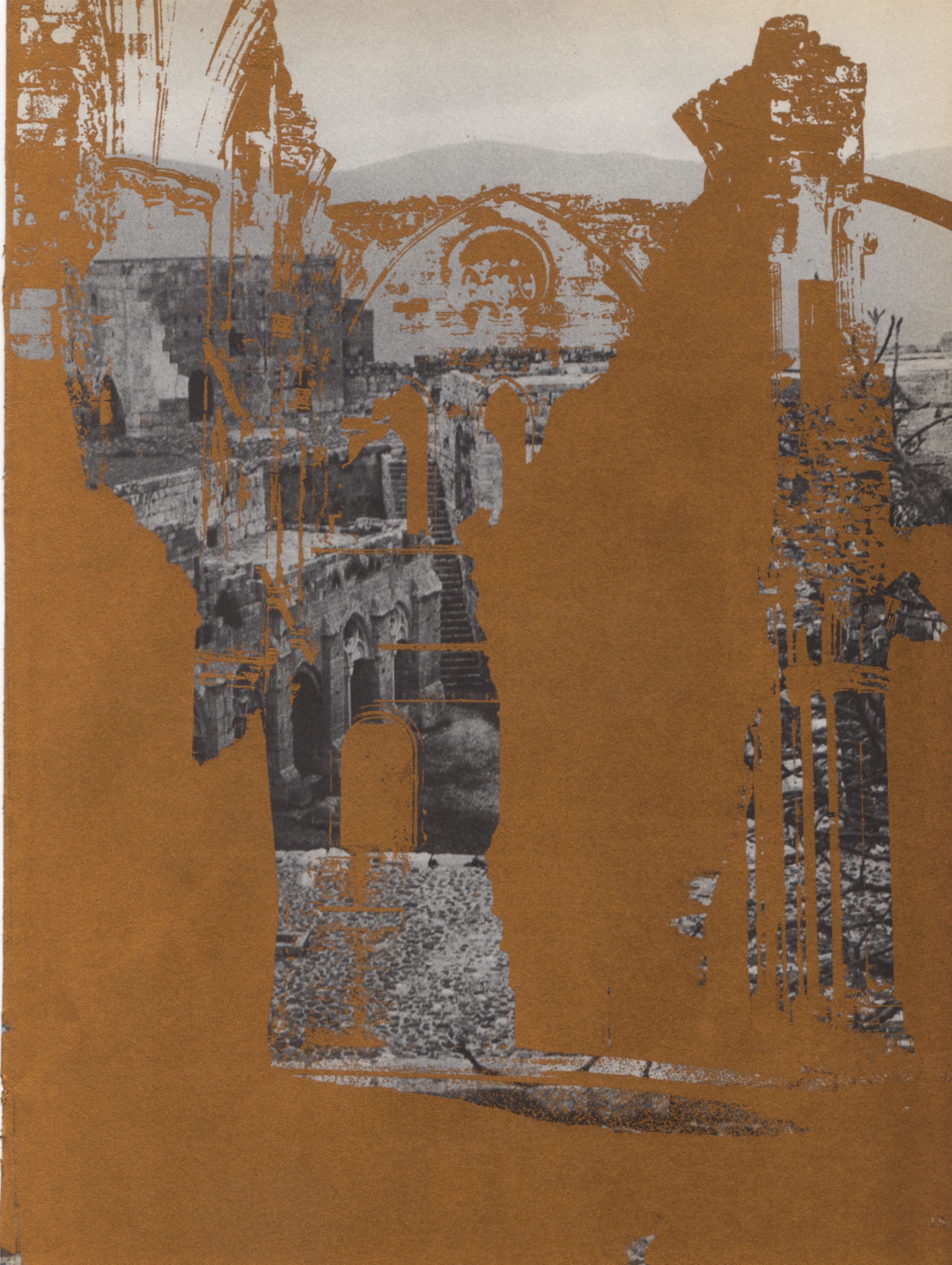

Pluta’s practice explores the disparity between spatial/temporal experiences and how these differences manifest themselves both visually and psychologically. The collection of works in Blue distance connotes the ways in which a specific past can be recorded, mediated and re-experienced. The works in the exhibition explore notions central to the construction of reality where the folly becomes a symbolic structure capable of manipulating an artificial paradise in which the viewer becomes lodged in multiple contexts simultaneously. These diverse components each play with the visual syntax of photography and objects: photo murals that resemble interior wallpapers depicting luscious vistas and panoramas (a medium that embodies a space through its association to a place and evokes the desire to be somewhere else); collages combining graph papers and photographic fragments that evoke the calculated logic of proportional values of the Golden Mean with scenes of prehistoric glaciers, mountains and caves; skeletal remains of shrubs; and a visual iteration of the 1977 edition of Roloff Beny interprets in photographs Pleasure of Ruins by Rose Macaulay. The original piece of literature was published in 1953 by Rose Macaulay and articulated the relationship between the disappearance of buildings and the desertion of words used to describe them.

Pluta’s practice responds to sites that evoke a longing for place–redundant structures and placeless landscapes–sites that appear universal and evoke temporality. Her interest in eye-catchers structures is pivotal to her concern with authenticating a past while querying the present. The possibility of imagining an alternative place, a mimic or fake, and playing out these allegorical relationships to actual prefabricated ruins is pivotal to this new work.

Blue distance highlights the ways in which Pluta utilises different mediums and diverse forms of imagery which relate to and overlap each other in tradition, function and materiality. This eclectic collection of works connote her conceptual interest in serendipitous encounters, the effects of time and how the photographic image operates as a vehicle for witnessing various states of ruin.